In this article, taken from The Ludgate Magazine (London, 1899), we have a veritable feast for collectors of TPOs. It is certainly unusual to see the operations of travelling post offices in the nineteenth century.

The postal system of the country may be taken as part and parcel of the railway, for the G.P.O. would indeed be a shortlived institution should it ever strive for indepenence.

In the year ending March 1894, we were informed that the number of letters, postcards, book-packets, circulars, samples, newspapers and parcels sent through the Post Office was 2,796,500,000 and that the bulk of this was transmitted by rail.

It is true that in the Parcel Post system the railway has to face a formidable competitor, for the Royal Mail coaches, a revival of the good old times, ply on no less than eight highways out of London, because it is found to be both a cheaper and more swift means of transit for this “expansion of trade” – the Parcel Post.

A writer on railway lore goes a step further and ventures to warn shareholders that the time may come when passengers will be accepted as parcels, having been subjected to an official stamp before embarking on the coacht – they would, in fact, be conveyed at “owner’s risk.”

It i s not generally known that the pneumatic tube plays a very important part of the G.P.O. system, more particularly as a night-messenger, in the newspaper office.

It is claimed that atmospheric air never loiters by the way to play marbles or “cod’em,” neither does the tube puncture or in any way lay itself open to the temptations and various hindrances which meet the experienced Press messenger or thirsting reporter.

The railways advertise, and are more than anxious for your custom. Parcels are collected free of charge, and possibly – not often – delivered in a state of chaos, free of contents.

Speaking of advertising reminds me of an accusation brought against a famous biscuit firm, to the effect that although the managers stoutly denied the charge of thus pushing their wares, it was proven, and that without a doubt, that not only did they imprint their name upon every biscuit, but in addition, made the public swallow it.

The whole world, it may be safely asserted, feeds from its postbag: if these rations are stopped, business, enterprise and progress are at a standstill, or worse.

How many of us picture the weather-beaten driver in charge of either mail coach with its steaming “three in hand,” or the frizzling engine-man in charge of the Travelling Post Office Down Night Mail, upon whose care our morning post depends; and yet it is to these faithful servants of the Government (not public, as they’ll tell you, if you proffer a bent halfpenny across the Post Office counter) that we owe so much.

But our object is briefly to explain the ingenious mechanism which the G.P.O. adopt, upon all the principal trunk lines of the United Kingdom, for the transmission of letters and the like.

The first illustration depicts the stationary post office at Bletchley Junction, the only one of its kind to be found actually on the platform of a station, but being so important a centre for the exchange of mails, the L. & N.W. Ry. Company found it expedient to control an institution of the kind.

This particular company, be it observed, is the Royal Mail route par excellence, providing as it does the special weekly American mail trains, and also the Irish.

The genial post-master stands to the right of our view, and within arm’s stretch we may notice various interesting impedimenta, such as mail canvas bags awaiting their consignment from the sorters’ tables in the centre, tall baskets for the reception of umbrellas, wicker bird-cages, or a pot or saucepan which, like the widow’s cruse, never fails to supply molten sealing wax for the purpose of official stampings upon the canvas letter-bags.

Above we notice the counter part of the station post-office.

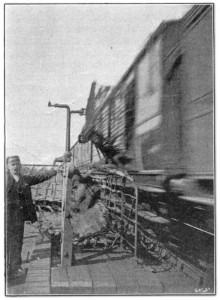

This is the T.P.O., or Travelling Post Office, which dashes headlong in the hours of dark from apparatus to apparatus, for the purpose of both delivering and picking up mail bags without a stop; in fact, at Bletchley, where most of our illustrations were secured, the speed is proved to be over a mile a minute: but for all that, the double exchange goes off nightly, and in the case of the weekly “specials,” to which reference has already been made, by day too, without a hitch.

The apparatus at Bletchley has recently undergone a change, and we find that while it has been moved about half-a-mile from its former position, the other side of the junction, we also notice that the apparatus is of the latest and most approved pattern.

Now about the Travelling counterpart of the post office. There may be two or any number ot bogie letter cars on the mail, and these are united one to the other by means of covered gangways giving the appearance of one long saloon.

We notice a net on the exterior of the carriage, and also some iron brackets fastened flush with the side of the vehicle, as is the case when the apparatus is thrown out of action.

More about this contrivance later.

We pass inside the vans, and observe that the whole is lighted by a double row of gas-lamps from the roof. There is an open passage along the centre of each van, while on one side are empty canvas letter bags hanging in thick clusters, and on the opposite side runs a sorting table parallel with the entire length of each car, having at intervals numerous canvas wells for the reception of all halfpenny stamped matter.

Above this table are pigeon-holes innumerable from end to end, piled one above the other. Beneath the sorting table are folding seats, resembling little music-stools, but a letter sorter never had time to test one yet.

Long before this night mail quits its terminus the postal cars become choked with myriads of letters, and the sorters set to work directly they embark to gorge and disgorge both bag and pigeonhole.

If then we are to travel on the L. & N.W., our departure is made from Euston, and it is but a few minutes before Watford is passed, where we find the first apparatus for catching and exchanging mail bags in readiness.

But it is at Bletchley, one of fifty-three stations on the system, where the heaviest bags are both dropped from the postal vans and received; therefore we will accompany the scarlet-coated mailmen who are just starting from the post office, with their canvas letter bags shouldered in readiness for the mile which they have to foot to the apparatus.

It is on the “Down” side where we find all the tackle, the “Up” side merely having a small receiving net to catch the drop from the mail, without giving any thing back in exchange.

We notice as we draw near that the apparatus is out of action, the lofty brackets or “standards” being reversed inwards from the line, and the receiving net closed, the iron barrier which is close to and runs parallel with the rails leaning against another of wooden construction.

The two mail-men have no time to lose, so they set to work at once to enclose the sealed canvas letter bags “in stout leather casings or “pouches.”

The weight of these pouches, when made up, must not exceed 50 lbs.; but then as many as nine such packages can be hung up for the mail nets to sweep off, seeing that each standard provides three spring catches whereon separate pouches can be hung.

One net is sufficient both on the ground and on the mail, as however many pouches are hung out from the stationary standards or even mail van, they are all of them bound to come in contact with the one receiving net.

The standards are next turned round with their precious burdens swinging aloft in mid-air, and the receiving net thrown open and propped up by means of a stout metal cross-bar which bearsthe full brunt of successive blows from the mail-van standards, thus releasing the pouches.

The net itself, of a size known as ten feet (and this is one of the largest to he seen), is of very formidable proportions; and so it need be, when we picture the shock received as the mail, travelling at seventy miles an hour, hurls nightly into the net something weighing quite threequarters of a hundredweight.

The train itself at the moment of the double exchange fairly staggers under the blow, and for the moment seems to halt, for proof of the concussion is readily understood when it is mentioned that the rails, which are laid parallel with the apparatus, require special attention, inasmuch as the line is periodically pulled round out of truth, entirely due to the impact which the long mail car causes (and the net is always at the end furthest from the engine) as courtesies are exchanged.

As soon as the mail comes in sight, within 200 yards of the apparatus the net is sprung by a lever in the car, and this operation is automatically announced by an electric bell, which continues to ring in the postal van until the catch is taken, and the net closed again as a warning to the sorters to give a wide berth to that end of the car where the net is situated, for the huge pouches that comeshooting in and rolling down from the net would fairly damage anybody.

Simultaneously with the dropping of the net, the hinged standards are let down by a cord from the side of the car with the leather-wrapped bags dangling and scudding a few feet above the fast-vanishing track.

The supreme moment then arrives, and mails are exchanged, but with such rapidity that the eye fails to follow the double movement which takes place. Inside the car, you are conscious of a tremor from stem to stern of the saloon, and a bang and a crash.

If you are standing near the ground apparatus, you are conscious of hearing a series of sharp, cracks, above the roar and grinding of the express, almost like the report from a volley of rifles, as one after another the nets pick off their complements, and nothing but the vanishing tail-lights of the mail are left to view.

Properly speaking, the mail vans should always be coupled next the engine, both as a guide to the mail-men in charge of the ground apparatus, and also for safety to passengers.

Horrible catastrophes have occurred before now, when the mail-van, with its net, and appurtenances, has been run in some other portion of the train – that is, anywhere but next the engine. In more than one instance a passinger has leant too far out of the window, when his head has come in violent contact with the huge pouches swaying on the standards of the ground apparatus, whilst if the mail-van had been run in its proper place these pouches would have been picked up before a passenger carriage could reach them.

The sorters, and there may be as many as twenty or more in the night mail, are some of them specialists at their work, while others take it in turns to have a ride as a change from the routine at the G. P. O.

An apparatus inspector who has been completely through the “mill” was telling me of the “sea-sickness” fromwhich at first all sorters invariably suffer. They are for a time completely prostrated, while it takes about three weeks to acquire one’s “mail-legs.”

The overseer in each sorting-car is responsible for the carrying out satisfactorily of all the many operations which require assiduous and unremitting attention. For example, the night mails would seem to afford increased difficulties by way of knowing where and when to, precisely set the van nets and drop the pouches, for, as it has been pointed out, should either ofthese operations be effected before or after the right moment, a long list of casualties may be the issue.

Above, thimbles strap and spring attachment on standard, closed and opened.

However, an experienced sorter can tell by ear to within a few yards as to whereabouts he is, and whether the moment has arrived for exchanging mails, his hearing being guided entirely by such sounds as the peculiar reverberation noticeable when rushing through a cutting, the roar when the mail burrows into a tunnel, or shoots under or over a bridge. It is true that there are other “cues” to act as a tell-tale, such as large white-washed landmarks close to the various ground apparati; but these are only useful for day mails.

It is the inspector’s duty to make a round of surprise visits, both to attend to the apparatus, which frequently requires repairing, and to, perhaps, see that the line adjoining receives some extra ballast owing to its displacement; or again, to see that the mail-men pay some sort of attention to the various regulations drawn up for the safety of both themselves and the mails.

A rather common mistake at one time was to hang up a pouch with its proportionate length sideways, instead of lengthways and parallel with the line. As a consequence, the mail net has struck the pouch, and, ripping up the tough bull hide, fairly scattered the contents and all to the four winds-odd scraps of paper were found for over half-a-mile up the line in too small a portion to make it worth the while of a professional scavenger to collect.

See the TPO & Sea Post Society website for collectors of TPO and RPO postmarks and covers.

If you enjoy reading our articles, kindly recommended us to your stamp collecting friends on your favourite social media…