The following article was written by Oscar Karl Goll and first published in “Stamps” (April 6, 1935).

With the 75th anniversary on April 3 of the founding of the Pony Express

The accompanying article has to do with a partial life story and the manifold trials and tribulations that beset California’s intrepid pioneer senior representative in the United States Senate, Hon. William McKendree Gwin, during the era that he championed and fought for his bill which sought the enactment of Fedoral legislation instituting the authorization of America’s new world-famed Pony Express, inaugurated during the temerarious days of the harassing and hostile Indians, and the almost daily murderous depredations of the road-agents who then infested what at that time was the untamed West.

* * * * *

Visioning during his lifetime the subjugation and then the development of a vast empire west of the Mississippi, United States Senator William McKendree Gwin (1805-1885) of California, that colorful and staunch member of the now famous Tennessee family, Cavaliers of the Old World, who so valiantly supported the cause of the Stuarts in the New, fought for and finally won, against overwhelming odds, his fight for better-mail and express service between St. Joseph, Missouri, and San Francisco.

The ultimate establishment of the Pony Express was due solely to the untiring and tenacious struggle waged by Senator Gwin, who in January, 1855, introduced his first bill in the American Congress. He sought the creation of “a faster weekly letter-express service between St. Louis and San Francisco.” The transit time was to be ten days, while the compensation to he paid to the carrying company “was not to be more than $5000 for the round trip.” It was further set forth in the bill that “the route known as the Central Route (by way of Salt Lake City and Sonth Pass), was to be followed.”

The bill, the paramount purpose of which was for closer communication with the East, was referred to the Committee on Military Affairs of the Senate, and there it died a natural death. The Southern members of the Committee, who looked with disfavor upon the Gwin measure, moved that it be pigeon-holed.

As time went on, the question of slavery occupied the attention of the Congress, but the people of the West, and particularly San Francisco, pressed their demands for action for a faster mail service with Eastern cities. All such petitions, however, met with little or no response, as the members of the Congress from the Southern States, through their combined voting power, were in a position to anticipate and defeat any possible legislation which might prove favorable to any routes north of the Mason and Dixon line, and thus assist with Federal aid only those routes operating through the slave-holding States of the South.

Senator Gwin, though balked at every turn, was not to be discouraged in his attempts, and, like the Southern-born gentleman that he was, kept right on hammering away at every opportunity, and, by so doing, succeeded in keeping his pet issue before his compatriots.

At the next session of the Congress, Senator Gwin reintroduced his original bill calling for the establishment of a faster mail-express route by way of Salt Lake City and South Pass, “in conjunction with the already operating Central Route.”

At this point, let it be remembered, there already were three transcontinental mail-express routes operating between California and the East (the Pony Express by no means being the first outfit to carry mail betwixt those localities), as the great bulk of mail matter and express was being carried by way of Panama from San Francisco to New York, and the time thus consumed, one way, was 22 days.

The operating companies at that time were the Butterfield Route, the Central Route, and the Chorpenning Route, all of which were favored by the Southern Senators and Congressmen.

As the question of slavery became more acute in the Congress, Union Senators began to manifest open and grave concern for all Governmental activities carried on via both the Southern Mail Route and the Panama Route, expressing fears of possible gross interruptions in the event of a sudden declaration of war between the Northern and Southern States.

It was pointed out by them that in the face of possible hostilities, it was of great importance to the North that immediate action be taken for quicker and more certain communication between the West and the capital at Washington.

At last Senator Gwin’s great opportunity was at hand, and, in an all-day speech on the floor of the Senate, he stressed the possible closing of all Southern mail routes, together with the vital importance of a speedier line of communication between “the peoples of the Sovereign State of California and the peoples of the East.”

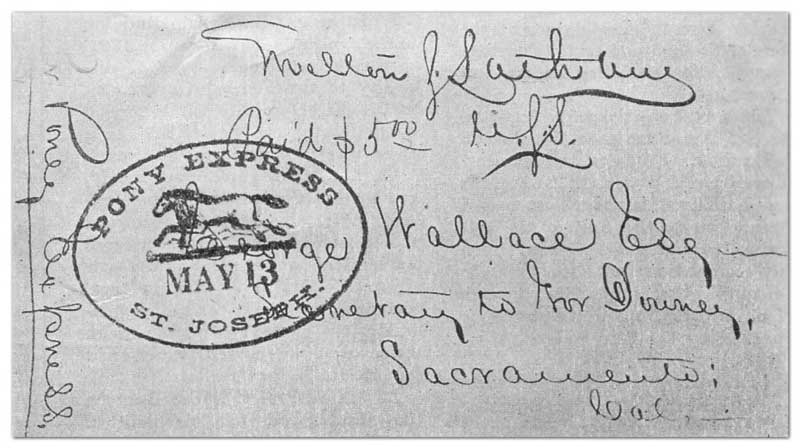

After a few weeks consumed by numerous Congressional committee meetings, and during the absence of several of its Southern members, the Joint Committee on Military Affairs was won over by the fervent pleas of Senator Gwin, and shortly thereafter the organization of the “Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company” (the Pony Express), was duly authorized to engage in business under the provisions of Senator Gwin’s bill, and some six “weeks later obtained a charter from the Legislature of the State of Kansas, said route to operate from St. Joseph. Missouri, to San Francisco.

The first Pony Express departed for San Francisco from St. Joseph on April 3, 1860, and the schedule allowed per trip was eight days. It was short lived, however, and ceased to function in the Fall of the following year, October, 1861, upon the completion of the Pacific Telegraph Company’s line through a major portion of the territory travelled by the Pony riders.

Even during its brief existence, the brave and fearless riders of the Pony Express were confronted with and encountered numerous dangerous hazards and even death, such as the following excerpts from newspaper articles of that day will testify:

“Bart Riles, Pony Express rider, died this morning from wounds received at Cold Springs, May 16.”

“Six Pike’s Peakers found the body of the Pony Express station-keeper, horribly mutilated, the station burned.”

“The Pony Expressman has just returned from Cold Springs, being driven back by the Indians.”

“The men at the Dry Creek Pony Express station have all been killed, and it is thought those at the Robert’s Creek station have met the same fate.”

And now, the concluding and most tragic part of our story has to do with a brief sketch of that venerable and grand old Senator of Southern birth – the father of the Pony Expres – who, history records, always maintained that “one should meet death as cheerfully as though it were one of the pleasures of life.”

Senator Gwin was born near Gallitin. Sumner County, Tennessee, October 9, 1805, and was graduated from the medical school of Transylvania University, Lexington, Kentucky, in 1828. He commenced practice in Clinton, Mississippi. Was United States marshal of that State in 1833, and elected as a Democrat

from Mississippi to the 27th Congress (1841-1843), and declined to be a candidate for re-election. He was a man of the strictest integrity and of the noblest impulses, and while in the Senate won a wide reputation as a debater, as well as a philosopher and statesman.

He joined the mad gold rush to California in June, 1849, and in the same year was elected a member of that State’s Constitutional Convention, and upon California’s admission into the Union of the States was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate, where he served from March 3, 1850, to March 3, 1861.

When he left the Senate Building on the expiration of his term in 1861, he was arrested on charges of disloyalty to the Federal Government because of his open declarations and sympathy for the South, and as a result was imprisoned for two years.

He felt his disgrace most keenly, and upon his release went to England. After a short time he returned to his native land, where he offered his services to President Jeff Davis of the Confederacy, who, in turn, commissioned him a brigadier general in the medical corps, and with which unit he served with great distinction.

At the close of the War Between the States, believing his political prestige gone, together with a huge fortune he had amassed from his gold mining properties in California, General Gwin drifted into Mexico, where he offered his sword to the Mexican Imperial Government of Maximilian, by whom, in 1866, he was designated by royal decree as the Duke of Sonora, and given extensive timber and land grants in that Mexican State.

With the downfall of the government of Emperor Maximilian, General Gwin renounced both his title and his lands, and returned to his adopted State of California.

He died September 3, 1885, while on one of his regular annual visits to New York City. His remains were taken back to the Golden State, where they now rest in Mountain View Cemetery, in Oakland.

And thus ends a chapter in the life of “a man whom fortune hath cruelly scratched.”

If you enjoy reading our articles, kindly recommended us to your stamp collecting friends on your favourite social media…